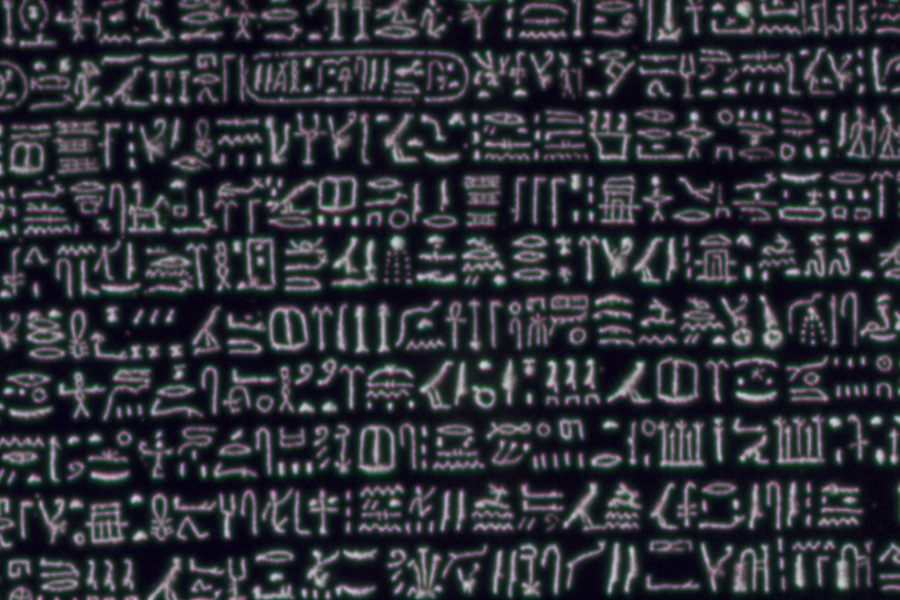

Teaching with inquiry can feel like this scene — especially in the back-to-school months of August and September. Social studies teachers look out into the eyes of a new group of students petrified that the inquiry bridge might not appear.

After all, inquiry is filled with unknowns. Teachers may have a solid inquiry curriculum stocked with compelling questions, sources, and tasks, but that is no guarantee that students will care about or engage with the material. And even if they do, there can be a palpable fear of losing control — what might students say in response to a question? Could the interpretation of a source land the teacher in an uncomfortable place? What if students get heated or offended by another student’s argument?