From Imagine Learning, I’m Lauren Keeling, and you’re listening to Heart Work, an honest profile of America’s educators.

Teacher 1: It’s exciting, terrifying.

Teacher 2: Nerve-wracking.

Teacher 1: Overwhelming. There are a lot of moving parts.

Lauren: What makes it overwhelming? What makes you feel a little nervous?

Teacher 3: It’s new and it’s a lot to take in. So we just go little by little, day by day.

Lauren: Does anything make you feel excited about taking this into the classroom next year?

Teacher 4: I’m so excited that we’re going to create a school full of readers. For our kids, it’ll be life-changing.

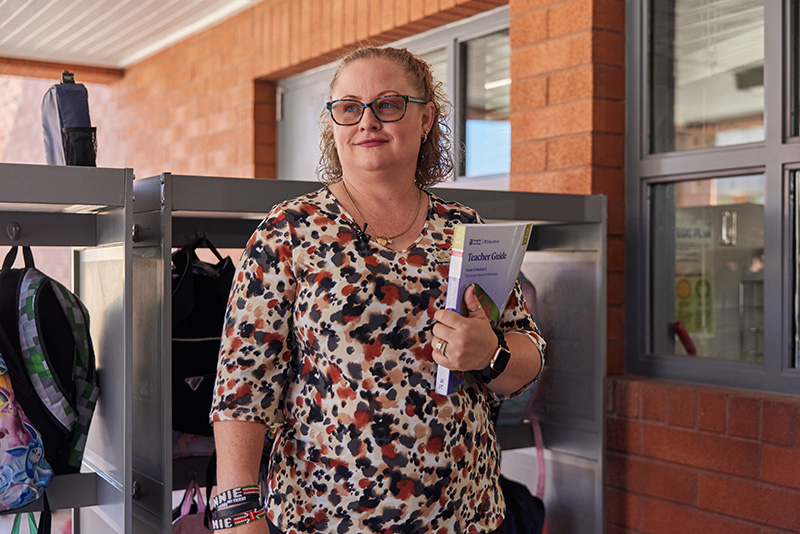

Lauren sits with a group of teachers as they share their thoughts on implementing new literacy practices.

In the United States, education is mostly managed at the state level — the system was literally founded on the principle of local control. And there are reasons for this.

The U.S. is vast and culturally diverse, with major differences state-by-state in demographics, economics, regional histories, and community priorities. Local control allows for decisions to be made with these contexts in mind.

But it’s also one of the reasons why change in education is slow. It’s never one change. It’s five.

With larger pedagogical shifts, progress can be even slower. And with the science of reading, it’s taken decades to reach the tipping point we’re at now, with more and more states adopting it into their reading instruction in an almost domino-like effect.

This isn’t just adopting a new curriculum; it is stripping everything we thought we knew down to the bone, fundamentally changing how teachers teach, how students learn, and how districts measure success.

But my own experience, both as a student and educator, is in a very small district. That’s why, today, I’m here in the School District of Philadelphia — the eighth-largest school district in the U.S. — to understand how a transformation like this plays out at scale.

It’s the middle of June and the beginning of summer break, and yet 600 educators have voluntarily gathered, ready, or at least willing, to rethink everything they thought they knew about teaching reading. For years, progress has been slow. And over time, it became impossible to ignore — and clear that something different was needed.

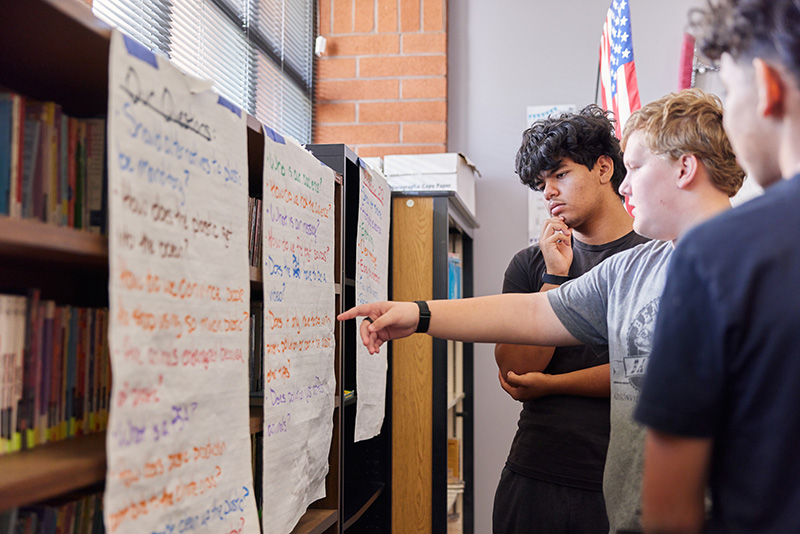

Educators walk through a school hallway during a break between training sessions.

Walking into the foyer of the school we were in for training, I’m shocked at the energy. I’m introduced to Antoine O’Karma. She’s the Director of Curriculum and Instruction for ELA.

I tell her I’m here to understand why they’re shifting to science of reading-aligned practices — a move toward teaching reading through systematic phonics, knowledge building, and other research-based methods — and how they’re making it work in such a big district.

She doesn’t miss a beat.

“Well,” she says, “then you have to talk to Erin Seroch.”

So I do.

Lauren Keeling: You and I were just having a conversation about just being educators and entering into a moment where we kind of realized we’d been teaching children wrong for a long time.

Erin takes me back to 2020. She was teaching second grade at Lingelbach Elementary School.

Erin Seroch: And then the pandemic hit. I listened to a podcast, Sold a Story. Bawling.

My husband’s like, “What is wrong with you?” And I’m trying to explain to him, and he’s like, “But Erin, like, you always get all distinguished on your observations and dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, and, you know, I don’t understand.”

And I’m like, “That’s great. I was doing what I thought was best, and I did that well. But I know this isn’t best for my kids, and I need to figure out what to do about it.”

I’m struck by how similar Erin’s story is to my own. She tells me about the moment she realized just how different these instructional practices were from what she’d learned in college. That realization is what led her to enroll in a course: Pathways to Proficient Reading at the AIM Institute for Learning & Research.

Lauren and Erin talk about their shared experiences and their paths toward evidence-based reading practices.

Erin: I saw brain MRI mappings — how kids learn how to read — and knowing that this is legit, we now have scientific evidence that this is what we need to do.

She realized that the practices backed by this research were very different from what she had learned in college.

Erin: I went back to my principal and I said, “We need to make some major changes.” We took the class together, and she was like, “OK, I get it. You’re right. I trust you. How are we going to make these changes?”

It was a good question. Adopting a new program wasn’t an option, so instead, they found ways to fold research-backed strategies into the curriculum they already had. And it worked.

Erin: Fast-forward a couple of years, and our proficiency levels went from 17% advanced or proficient on the third-grade ELA PSSA, all the way up to 79% on one school year.

Soon, people throughout the district noticed Lingelbach’s 750% growth rate. And they wanted to know what changed.

For many educators, it was data just like this that shifted their mindset. But it wasn’t just the numbers. It was the emotional piece, too. Teachers were watching their students move up to the next grade level still struggling. They were hearing their colleagues saying, “Hey, this kid is still having a hard time.” That experience pushed them to reconsider what was working.

They started reflecting on their practice. Then listening, and researching, and campaigning, and slowly, things changed.

And that is exactly what happened in Lingelbach, and it started with teachers like Erin.

My conversation with Erin led me to Megan Gierka and Nicole Ormandy. They were giving a keynote speech at the training on science of reading best practices, so I got on a call with them afterward to talk about their experience in Philadelphia and about their work supporting educators.

Lauren: So 600 teachers are learning this brand-new system; they’re learning all of these new theories, and models, and practices, and trying to get it ready to take into their classrooms in a short amount of time. Talk to me a little bit about how both of you support leaders and educators at an event of that scale.

Megan Gierka: We hardly ever walk into a room where we don’t know our audience really well. So part of our work comes in not just when we get on the stage and you hand us the microphone, but in getting to talk to those teachers and those leaders for months before we ever walk into that room — getting to know what curriculum they’re using, what assessments they’re using, what their current barriers are.

I live about an hour and a half from Philadelphia, and the schools where I taught have very different barriers than they do. So making sure to address what they’re uniquely facing when we’re in the room — but also making that research make a lot more sense.

Lauren: Let’s say that a teacher is listening to this, and he or she doesn’t have access to the two of you. Could you talk to me a little bit about how they might approach it themselves.

Nicole Ormandy: There’s unfortunately no quick fix. This is new. This is work. This is a lot of knowledge to be gained, but extremely rewarding knowledge to be gained, because what happens next, once you have that knowledge, you’re then a critical consumer.

You can be handed any curriculum, and you can evaluate: Yes, it teaches this element; no, it doesn’t; my students need it; it didn’t include it; I’m going to annotate this.

So it’s not reinventing the wheel on a strong curriculum, but it’s definitely making it extremely targeted and applicable for your audience. We can’t expect every curriculum to know every student population and to know them better — know your students better — than you.

And so that’s where that comprehensive training is preparing you to evaluate your curriculum, your assessment data, and really make use of it extremely intentionally.

Megan: Being able to discern some of the reputable and not-so-reputable resources and frameworks is so critical. So something Nicole and I live and die by is the International Dyslexia Association’s (IDA) Knowledge and Practice Standards. Nicole and I have collaborated with the IDA in the past. A lot of people think that it’s just for students with dyslexia, but really, it’s for all teachers of reading, which, by the way, is everyone. Everyone who teaches a child is a teacher of reading, writing, and literacy.

Lauren: How does the administrator or the literacy coach fit into this puzzle?

Nicole: The leaders and the administrators are driving this ship, right? It is completely unfair and ridiculous for teachers to go through training that leaders haven’t gone through, or that leaders don’t know about, or that leaders don’t understand why the teachers are doing it, and what they expect to get out of it.

Megan: Thinking to Thomas Guskey’s approach — what does it take to make an impact in a system? Student outcomes are a level five. So what we saw when we were in Philly was that level one, initial reactions to learning or to a system change.

You start to see, over time and through the years, some of those higher levels of transfer to practice and student outcomes. I think sometimes leaders get antsy because they don’t see them in three weeks or three months, and they’re quick to abort mission when really it is a process to even get to those enhanced outcomes.

In 2013, Mississippi passed a law requiring schools to use research-backed instruction and materials. It was a desperate attempt to improve their reading scores. At the time, they had the lowest percentage of fourth-grade students reading on grade level.

Jump forward to 2019, and Mississippi made the most gains in fourth-grade reading in the country. The results speak for themselves; they’re remarkable.

But it would definitely be an oversimplification to say it’s all due to the introduction of new legislation. It took an incredible collective effort and a clear strategy that district leaders, educators, and parents equally bought into. Their success inspired other districts to adopt their own strategies, like the ones currently underway in the School District of Philadelphia.

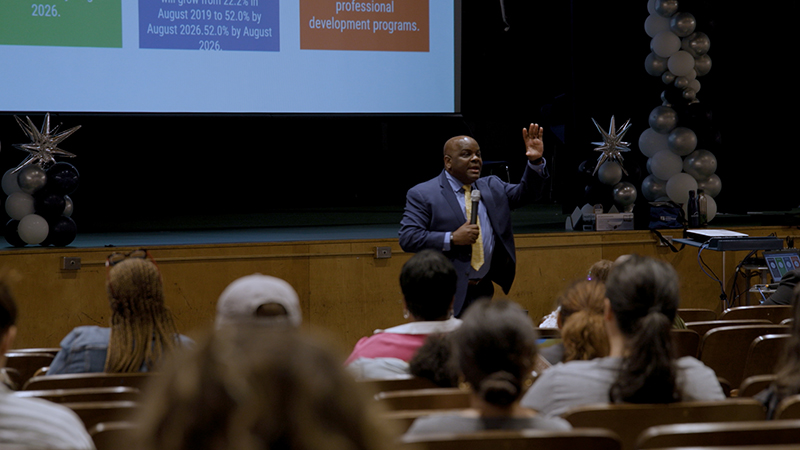

Dr. Dawson speaks to an audience during his keynote presentation.

Dr. Dawson, the district’s deputy superintendent, is helping lead this strategy. He is also attending the training event to deliver a speech, and I catch him right after to talk.

Lauren: Dr. Dawson, your keynote speech was incredibly inspiring and spoke beautifully to the mission of the School District of Philadelphia. Why is this important?

Dr. Dawson: It’s so important that our students are able to read — and read at high levels. Not so much because of the foundational literacy pieces — but what does that mean for them in their future when they turn that tassel, as I say, and graduate 12 years later? The question we need to ask ourselves is, “Do they have the skills to be able to be successful in life, that will set them up for a limitless future?”

I’ve been on both sides. I’ve learned as a student using foundational literacy skills — or structured literacy — and then I’ve also been trained in whole language.

And what we see is that our students, by the time they get to high school, still struggle with the ability to effectively decode words. They don’t have the foundational strategies to attack that word, and that then creates a problem with comprehension.

And what this will do — through structured foundational literacy skills, phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, the automaticity that comes with fluency that builds comprehension — is allow them to take those skills and tools and start to read more advanced texts, moving from learning to read to reading to learn.

Dr. Dawson shows his students exactly who he is, where he comes from, and what he overcame.

Lauren talks with Dr. Dawson after his keynote presentation about the importance of literacy.

Dr. Dawson: I, myself, grew up in severe poverty. I experienced homelessness — eating out of trash cans, not knowing, and sleeping on porches — but one thing that I got was foundational skills in reading that set me up. I was able to read books that took me on journeys beyond where I was living every day and showed me a world that was bigger than I ever could have imagined.

And that inspired me and motivated me that I can see more and do more and want to see more. And because of the foundational skills that I received, I was able to go off and be where I am today as a deputy superintendent of academic services.

In the School District of Philadelphia, our goal is to give the students the skills and tools they need to be successful, so that they too can have that future — just like I have.

It’s late in the day, and we’re all feeling it. But there’s one more person I need to speak with to fully understand how a district of this size navigates a change like this: Antoine.

Lauren and Antoine sit in an auditorium, smiling and holding hands in a moment of shared emotion.

She had been one of the voices pushing hardest for change, and she’d helped put together this massive training session.

Lauren: So in designing this week and making the commitment to change and in working to support educators, how are you helping them learn what the science of reading really feels like?

Antoine O’Karma: We’re not just starting this week, right? We’ve been working with teachers for four years now. And I think showing connections, right? Not saying, “OK, everything you’ve been doing is wrong. It’s bad,” right? We have such smart teachers, such veteran teachers, and it’s not like throwing the baby out with the bathwater, right?

Antoine emphasizes that the training must go beyond focusing solely on pedagogy. Teachers need to leave with a clear understanding of how the research translates into practical application and how new instructional strategies build on their existing knowledge.

She acknowledges that the change won’t be easy or quick — but that ultimately, it has to happen.

Antoine: But if we can show through data that this is why we’re doing it. We cannot be happy with 38% of our children reading on grade level.

Lauren: I wonder what you would say to someone who is going to tell you that the School District of Philadelphia can’t make this change — can’t turn it around, can’t change those scores.

Antoine: I would say, let’s look at our data. Let’s look at how our data has changed. The data doesn’t lie. We’ve had some amazing results for schools and teachers who really bought in, honed their knowledge, and are committed to this work.

As educators, we often want to see results immediately, but that’s not how it works.

It takes at least three years to fully implement any kind of change practice and see results. And the first year is always the worst. That’s just the truth.

We also have to acknowledge that research is not fixed. It doesn’t point to one answer and say, “This is it forever.” And that doesn’t mean the research is wrong or ineffective, quite the opposite — that’s the point of research: To continue to learn.

In the School District of Philadelphia, they’re in it for the long run.

But this is not my biggest takeaway from my time there. What is, is how influential teachers were in starting the change movement and how deeply they believed in it — and that is really crucial to finding success when making real change in the classroom.

A group of educators pose for a photo.

Megan: Frederick Douglass said that once you learn to read, you will be forever free.

If we can give this gift to our children, they will have lifelong success as a result of that precious school year we had with them.

Nicole: You can do this. You can do this. It matters. Don’t be afraid. Be empowered. Knowledge is power, right? So get in there, get your hands dirty, and learn this work. Start making the change, because you deserve it. Your kids deserve it. And, like Megan said, it’s freedom.

Next time, I’ll be heading back to Pendergast Elementary School District to see the culmination of three years’ worth of dedication to improving reading scores. I’ll also be talking to education writer Natalie Wexler about the critical importance of knowledge building.

Natalie Wexler: We have to stop seeing reading as separate from learning — than the content areas — as if reading and writing both are separate from each other. They really are not. We know that when kids write about what they’re learning, it boosts their reading comprehension. It deepens their learning. These things are all connected.

All that and more on the next episode of Heart Work.

Want to put faces to the voices you heard today? Join me on YouTube at Imagine Learning to meet the educators featured in this podcast, and don’t forget to check out my reading list linked in the description, along with a link to Megan and Nicole’s podcast, Reading Recess.

This episode of Heart Work is produced by Justyna Welsh, Anise Lee, Danny McPadden — and me. Editing and mixing by Fraser Allan. Our recording engineer is Dan Victory. Our set supervisor is Tyler Kavanaugh. Artwork by Ellen Forsyth. Our executive producer is David McGinty. Music is from Universal Production Music. Special thanks to the School District of Philadelphia, Erin Seroch, Dr. Jermaine Dawson, and Antoine O’Karma for welcoming us at the Summer Institute, Megan Gierka and Nicole Ormandy, and the educators who spoke with us for this episode.

Heart Work is brought to you by Imagine Learning.